Managing Financial Liabilities after death in India

4/3/20253 min read

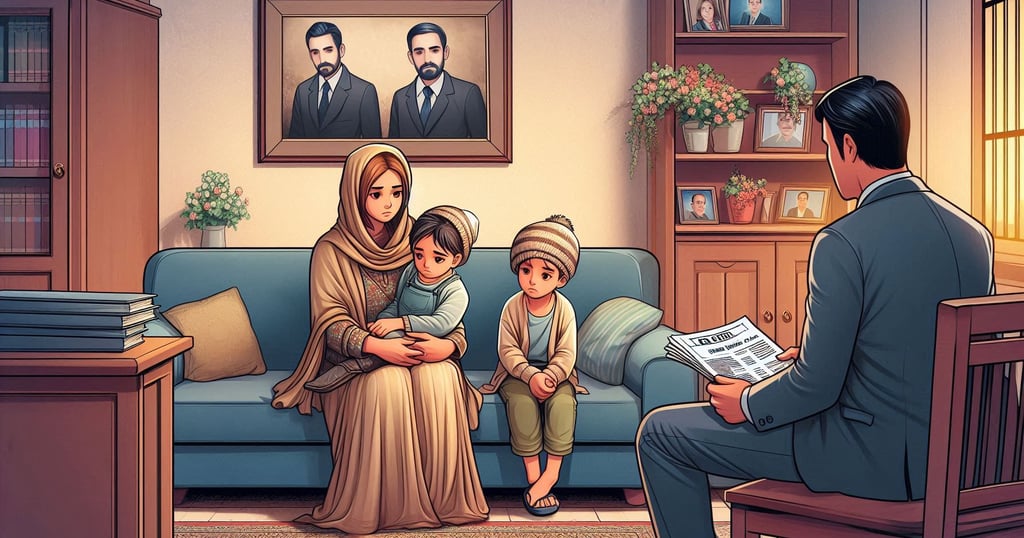

Death is an inevitable part of life, but its financial implications often leave families grappling with more than just emotional loss. In India, one critical question that arises is what happens to a person’s debts after they pass away. Understanding debt obligations after death is essential for both the deceased’s family and creditors, as it involves a mix of legal provisions, cultural practices, and financial realities. This article explores how debts are handled posthumously in India, offering clarity on liabilities, inheritance laws, and practical considerations—all within a concise five-minute read.

When an individual dies, their debts do not simply vanish. Instead, they become part of the deceased’s estate, which includes all assets (like property, bank accounts, and investments) and liabilities (such as loans, credit card dues, or mortgages). Under Indian succession laws—primarily the Hindu Succession Act, 1956, for Hindus, Sikhs, Jains, and Buddhists, and the Indian Succession Act, 1925, for others—the estate is first used to settle outstanding debts before any distribution to heirs. This means #creditors have a legal claim on the deceased’s assets, but only up to the extent of what the person owned at the time of death. For instance, if someone leaves behind a house worth ₹50 lakh and a loan of ₹30 lakh, the house may need to be sold to clear the #debt, with the remaining ₹20 lakh distributed among heirs. However, if the debt exceeds the estate’s value—say ₹60 lakh against a ₹50 lakh estate—creditors cannot pursue the heirs’ personal assets to recover the shortfall, unless specific circumstances apply.

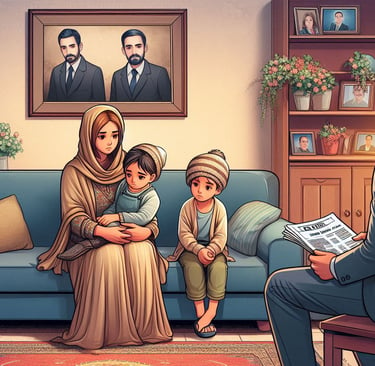

A key exception arises when heirs voluntarily assume responsibility for the debt or co-sign a loan. In India, personal loans, credit card debts, or home loans often involve co-borrowers or guarantors, such as a spouse or child. If the deceased had a co-signed loan, the surviving co-borrower becomes fully liable for repayment, regardless of the estate’s value. For example, if a father and son jointly took a car loan and the father passes away, the son must continue repaying it from his own income, not just the father’s estate. Similarly, if the deceased pledged an asset (like gold or property) as collateral, creditors can seize it to recover dues, even if it was intended for inheritance. This underscores the importance of understanding loan agreements and their implications before signing.

#Inheritance laws further complicate the picture. Under the Hindu Succession Act, legal heirs (like children, spouse, or parents) inherit both assets and liabilities proportionally, but only to the extent of the estate. If no assets are left after settling debts, heirs are not obligated to pay out of pocket—a principle rooted in the legal maxim “no one is bound to pay the debts of the dead beyond the assets received.” For Muslims, governed by Sharia law, debts must be cleared before inheritance distribution, often prioritizing creditors over beneficiaries. Christians and Parsis, under the Indian Succession Act, follow a similar estate-settlement process. However, in practice, families may feel morally compelled to repay debts, even if not legally required, influenced by societal norms or to preserve the deceased’s reputation.

Secured versus unsecured debts also play a role. Secured debts, like a mortgage or car loan, are tied to specific assets, which creditors can claim if payments stop. Unsecured debts, such as credit card dues or personal loans without collateral, rely solely on the estate for recovery. If the estate is insolvent, unsecured creditors may end up with nothing. Insurance can act as a safety net here—many loans in India come with credit life insurance, which clears the debt upon the borrower’s death, sparing the family additional burden. For instance, a ₹20 lakh home loan with such a policy would be paid off by the insurer, leaving the house free for heirs. Without this, the family might lose the property to foreclosure.

Practical steps can ease the process for survivors. Maintaining a will that clearly outlines assets and liabilities helps executors settle debts efficiently. Families should notify banks and creditors promptly after death, providing a death certificate to freeze accounts and prevent further interest accrual. Debts cannot be pursued indefinitely—under the Limitation Act, 1963, creditors have three years from the last payment or acknowledgment to claim dues, after which the debt becomes time-barred. However, disputes often arise, especially with informal loans from relatives or local moneylenders, where documentation is scarce.

Ultimately, debt obligations after death in India hinge on the estate’s value, legal agreements, and the family’s choices. Heirs are not automatically liable for personal repayment unless they co-signed or inherited sufficient assets. Awareness of these rules empowers families to navigate financial challenges with confidence, ensuring the deceased’s legacy isn’t overshadowed by unresolved liabilities. For tailored advice, consulting a legal or financial expert is wise, as individual cases may vary based on religion, loan terms, and estate size. In a country where familial duty often intertwines with legal boundaries, clarity on this topic is a vital tool for closure and security.

Registration Granted By SEBI (INA000020208), Membership Of BASL (BASL2266), And Certification From NISM In No Way Guarantee Performance Of The Intermediary Or Provide Any Assurance Of Returns To Investors. Investment In Securities Market Are Subject To Market Risks. Read All The Related Documents Carefully Before Investing. We are Fee Only Advisers. We prioritize customer over commission.

Copyright © 2025 Neha Sinha - All Rights Reserved.